This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Acts recounts the events of the spread of the gospel from Jerusalem to Rome and Mark Powell describes this book best. “The book of Acts has everything but dinosaurs. It’s got earthquakes, shipwrecks, avenging angels, harrowing escapes, riots, murder plots, political intrigue, courtroom drama, and so much more…”

It is a history book.

It is a theological work.

It is also an entertaining adventure tale.

Tradition holds that the author of Acts, who it seems also wrote Luke’s Gospel, was a physician or artist. Perhaps Luke was both. Stories capture the imagination of their listeners, and in skilled hands can speak deep, deep truths. Luke uses stories to their full power – just before this story of God raising Tabitha from death through Peter, Luke had told the story of a paralysed man, Anaeus, who was healed and able to walk. (This fresco, by Masolino, depicts the healing of Aeneus on the left, and Tabitha on the right).

These are just two of the amazing and powerful stories in Acts, that speak to God’s power and desire to restore people live full lives in their church community. These are stories that are skilfully woven by Luke, the physician and artist.

Anaeus was also the name of a popular character in an epic poem in Luke’s time. One hundred or so years before Luke wrote Acts, there was a Roman storyteller called Virgil who captured the imaginations of his readers with his compelling writing and poetry. Like Luke, Virgil also trained in Medicine, as well as Mathematics – double and triple threats were clearly a thing amongst the ancient elite. Sometime in the three decades before Christ, Virgil penned a famous epic poem, called Dido and Anaeus, that has been translated many times, turned into an opera by Purcell, and is still read today. The elite would have enjoyed reading and hearing it, and the characters influenced art works and performances more generally. The name of the title character will give you some clue why I’m giving you the Cliff’s notes, or perhaps the YouTube highlights reel, to the story now, so let’s settle in for the story of Anaeus and Dido, as told in Rome.

Dido was a mythical heronine who shrewdly captured the City of Carthage from the locals of what is now called Tunisia. On the run from a priest of Hercules who was determined to kill her, she escaped, and bartered with the locals of Carthage for supplies, negotiating to receive what could be contained within the skin of a bull in return for a substantial amount of her wealth. This excellent deal turned sour for the locals, as Dido shrewdly cut the skin into strips, and laid them around the hill of Carthage where she then reigned as Queen and settled in safety. Here Virgil picks up her story, and introduces her to Aeneus.

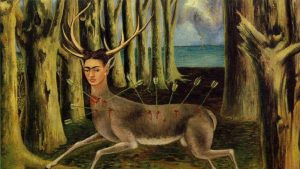

But Cupid had mischief in mind, and Virgil sets the scene for us by introducing Dido as a deer, wounded by an arrow. What could this mean?

Cue Aeneus. Aeneus was a military hero, who survived the defeat of the Trojan war with the Greeks, and now lead the remnant who escaped. Leaving the ruins and flames of that war, Aeneus is informed in a vision that his fate is to establish a new city and glorious Roman destiny. The Greek victory was to be a temporary incursion in the destiny of Rome.

Aeneus moves towards his destiny, and a series of supernatural and natural events lead him to the Libyan coast, where his ship meets terrible weather, and is forced to land. There he meets the Carthage Queen, Dido, and Dido listens to Anaeus’s astonishing tale, and falls in love.

Dido and Anaeus go hunting, but catch nothing. They retreat for a while into a cave, where their mutual love is honoured in a mock marriage ceremony.

But this is a tragedy of the grandest scale in the making. No deer was killed when they hunted, because it is Dido herself that is mortally wounded.

(Let’s imagine that Frida Kahlo speaks to the pain of Dido in this self-portrait).

Dido believes the union is one of total commitment. Anaeus knows this is love without the possibility of commitment. Anaeus leaves her to fight, abandoning her at the command of God of Sky and of Rome, Jupiter. He will tear himself away from his beloved, to continue his destiny to establish the great Roman city.

Haunted by her love and loss, Dido takes the sword Anaeus leaves behind, and falls on it. While her death is at her own hands, there is no question that Dido’s cause of death is Anaeus’s abandonment.

This beautiful, shrewd, and lovely Greek queen is collateral damage of imperial aspirations.

The moral of Virgil’s story is that Dido and her love and attachment must be fought off to enable Anaeus to achieve his military destiny.

Virgil holds both Dido and Aeneus as heroes, and this tragic event was an unavoidable calamity of conflict between the Gods of love, wealth, and war.

In Aeneus, Virgil portrayed the qualities of persistence, self-denial, and obedience to the gods that, to the poet, built Rome. When Aeneus died, his body was not found, which elevated him to the level of a God in the Roman world. The family of Julius Caesar would later claim lineage from Aeneas, and define their own story by this tale. Aeneas is the story of Rome.

And Aeneas – the best of Roman Imperialism – leaves Dido and love for dead.

So, the question must be – what clue is being left by Luke naming the paralysed man Anaeus?

Luke was well educated, and draws on his education with this quiet wink to the famous work of another doctor and writer. It’s a bit like when JK Rowling calls her sharp and frightening teacher Severus, or the quirky character Luna. The name brings to us the association with Virgil’s poem, and all it tells us about Rome.

Our Gospel reading today introduces another person to be healed by their name – Tabitha, also called Dorcas. Why would Luke translate Tabitha for his Greek readers? There are lots of theories, but consider this – Tabitha – an Aramaic name, and its translated Greek version – Dorcas – means Gazelle or Deer.

Where Virgil’s Rome left the wounded deer, Dido, for dead, and accepted her loss as collateral damage, Luke’s church looked to God to restore the wounded deer Dorcus back to the community. Her gifts of kindness, compassion, and clothing for the poor were upheld by the community and Peter raced to her side when she fell. The story is being re-written again.

Luke replaces the Roman legend of imperial greatness with the story of Jesus’s compassion and inclusion, and the greatness of God’s love.

The of this story is not Peter. The hero of Acts is the Holy Spirit, and the Gospel itself. The Gospel message – the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus – ring true when spoken by those that live the life of Christ. Here we have a community that called to Peter not to restore their most powerful or effective leader, but to mourn the respected and charitable woman, that sewed for those who had nothing. It was this woman that God chose to restore.

Tabitha is the exact person who would have been left for dead in the wake of a culture with an insatiable need for wealth, land, and power. That consumed all before it, and left survivors to conform. That took the even the small amount of resources and security of those conquered and redistributed it to the highest. In Christ, we don’t have to settle for being collateral damage in the path of a mighty warrior God. Experiencing love isn’t to become a target for an arrow by the mischievous Cupid. In Jesus – love and community wins.

Doctor Luke and Doctor Virgil both diagnose the malaise and malignancy that is imperialism. Virgil sees the poison, Luke recognises the antidote.

For us today

Who is it today that is being left behind, for dead?

Who is it today that is discarded and demolished, left for dead by the constant need for growth, the acquisition of land and wealth, and power?

Once we see who our Tabitha is, we can ask ourselves:

What does it mean to be the church founded by Peter, modelled on Jesus?

Who is the deer today to whom we race, and reach out as God restores them to wholeness and our community?

How is God rewriting the story of our time?

Every blessing,

Reverend Ann

For more detail about today’s sermon, see the source:

Michael Kochenash. (2018). Political Correction: Luke’s Tabitha (Acts 9:36-43), Virgil’s Dido, and Cleopatra. Novum Testamentum, 60(1), 1–13.